August 10, 2017

If you walk into a restaurant and ask to buy a typical meal, it will probably cost you somewhere around ten or twenty dollars. If you asked to buy ten of that same meal, it would cost you about ten times as much. We consider this ten fold price increase to be fair because the average person understands that if you buy ten meals, the business owner needs to buy ten times as much food supply, and the server must do about ten times as much work to prepare, deliver, and clean up after you have finished.

This basic tenant of 'fairness' in pricing is fundamental to our sense of satisfaction when participating in a market economy. Even in cases where a price might be seen as too high, or exploitative, most people would generally agree that the high price will either be corrected by a lower price offered by a competitor, or simply by moving to a different time or place where the cost is more reasonable. In this case, even exorbitantly high prices can be seen as somewhat fair since one can reason that the seller is simply being rewarded for having their goods or services in the right place at the right time, which for the most part, is an opportunity that is equally available to anyone motivated enough to pursue it.

Lately though, I've become increasingly aware of pricing models that fail to pass the 'fairness' test by varying degrees. If a vendor wanted to sell bottles of water to you based solely on how much you needed it, say at $100.00 for anyone about to die of thirst, and $1.00 for everyone else, most people would agree that this isn't a very 'fair' pricing model, since it has no merits with the cost of the product or service itself and it has equal burden to the vendor in either case. Regardless of whether such a pricing model may be legal, the point is that it builds resentment and most people would agree it's not desirable to have a society that works this way.

The question of fairness starts to get murky when you consider anything that involves economies of scale: The raw business cost of allowing a first customer to make a single phone call from Canada to China is many billions of dollars due to the cost of building the vast telecommunications network required for the call in the first place. The second call costs effectively zero by comparison, and similar is true for the many millions of customers you add after that. In this case too, it's not too difficult for most of us to reason that it's still relatively fair for us to pay $50 or so dollar per month for access to the phone network. We understand that each customer's money is pooled to support the rather large aggregate cost of the infrastructure, and if none of us agreed to this payment model, then the telephone network would not be able to exist in the first place. In this situation, there is a physical constraint that the telephone infrastructure provider must overcome in order to provide us with what we are paying for.

Where pricing fairness starts to go completely out the window is in situations where there is no relationship between the pricing model, and the vendor's burden of providing whatever we are paying for. In other words: Situations where the vendor creates artificial barriers that did not need to exist in the first place in order to provide us with what we want. Sometimes, it's just hard to see the real physical constraints that the vendor has because of economies of scale, but my observation is that the justification of what we're actually paying for is becoming weaker and weaker.

When I log into my bank web site now, I see a message that says "a fee of $1.50 will be charged in the currency of the account for each cheque view. The fee will be debited from your account the next business day. You may view the same cheque as many times as you wish during your EasyWeb session at no extra cost." As a web developer, I can tell you that there isn't very much extra effort to display the cheque to you than there is to display the bank's logo on every page that's always there for free. The image of the cheque is processed and stored by the bank regardless of whether you look at it or not, and the bank already gets to charge you money for buying the cheques, but also for cashing them as well.

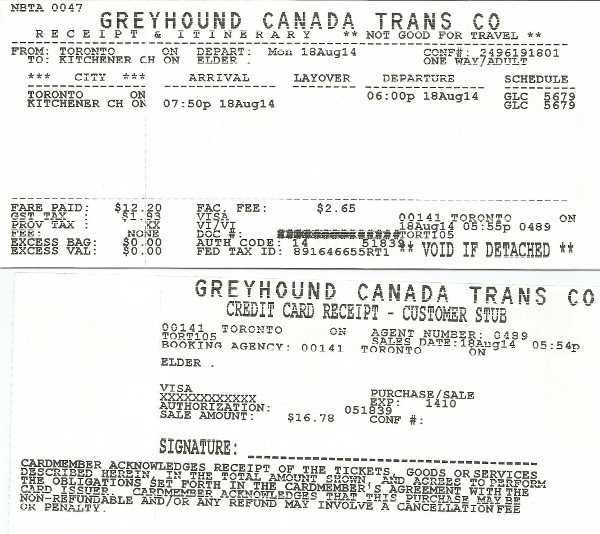

Here is a Greyhound bus ticket that I bought a couple of years ago:

Before I bought the tickets, I checked their web site and found that the tickets cost around $12.00. After buying the tickets, I find out that there is an extra 'FAC' fee of $2.65. Not a big deal, but what's this extra fee about? After some Googling, the internet claims that this is some kind of facility improvement fee that they charge when you buy the ticket at a physical location. But I didn't make use of the facility? If you add the cost of the fee to the base price of the ticket, and the HST, the total comes to 16.43, not 16.78. Turns out they charge HST on top of the 'FAC' fee, but don't bother to write that on the ticket.

If you've ever flown with any airline, you already know about my next example: 'Airport Improvement Fee', 'Convenience Fee', 'Fee Fee'. As of today, I'm checking Pearson Airport's list of fees page. It turns out they even have a special 'Connecting Passenger, Airport Improvement Fee' of $4.00. This way you can pay a fee for visiting an airport that you didn't even want to visit in the first place.

eBooks are another good example: They're substantially more restrictive than the original print media it was designed to replace. With these, you'll find lots of pricing models that impose artificial constraints based on the number of and type of devices you want to download them onto. These restrictions don't fundamentally need to exist, and it is in fact extra work to actually implement them.

Because our idea of what a 'fair price' is has been slowly eroded by the presence of economies of scale and their complex veil of technology, the logical conclusion is that companies will eventually develop pricing models that charge people whatever they want, whenever they want, simply on the basis of you being able to pay them the amount that they want. Direct price discrimination based on a person's income level isn't likely to be legal, but that's OK! Just make up some kind of 'We Want Money So Give It To Us Fee'.

But why would people pay money to support a system that presented manufactured problems that didn't exist in the first place? That brings me to one of the main points I want to make in this article: People are losing touch of what problems are real and which are manufactured in the first place.

If you buy movie tickets online now, you'll likely get charged an extra 'convenience fee' for doing so. But that's fair, right? You paid more because someone had to build that site, and it costs money to host it... But wait, wouldn't they actually be saving money by having you buy it online? A large movie theatre chain only needs one web site, but would need hundreds of ticket agents. Surely, the web site costs less to maintain than hundreds of extra employees. Are you really paying them money because it helps them provide better service, or are you paying them money so they can make more money?

Keep in mind, that I'm not actually certain that we'll end up with a dystopian outcome, and it may be the case that market forces eventually start favouring more ownership and control for the consumer again. Having said that, here are a few things to think about:

People complain about income inequality a lot these days, and with the exception of the minority who break the rules to win, most people would agree if you work harder you should have a higher income. In this respect, you can have unequal incomes but still have a somewhat 'fair' economy. Even if you disagree, it isn't likely that enough people will start rioting in the streets because their neighbor makes twice as much as they do. However, what is likely to upset people is constantly being bled dry by random fees, surcharges, and taxes of a system that makes absolutely no sense to them and automatically adjusts to rid them of the little money they have. This, I claim, is where it looks like we're headed. This hasn't been possible historically because most people were able to understand the society that they lived in. Something like a retail store couldn't control how people used their products in the comfort of their own home. However, if you put a microchip in everything and hook it up to 'the cloud' you can sell functional products that refuse to work unless you pay for a subscription.

Oh, Since I wrote this article mainly to share with my friends, I should mention that I'm moving to a subscription friendship model from now on. For $9.99 per month you get the Starter Friendship Package™. This comes with the standard regular email updates about my life, and no more than one personal email communication per month. If you really want to level up our friendship, you can subscribe to the Premium Friendship Package™ for $99.99 per month. The Premium Friendship Packages™ comes with everything the Starter Friendship Package™ offers, but in addition you get unlimited email communication with me. In addition, the Premium Package comes with sincere[1] feelings of caring and friendship toward you. In the event that you become extremely ill and end up in the hospital, you'll get one free[2] visit from me once per month!

[1] Not actually intended to be a legally binding commitment. Actual feelings of caring and friendship subject to change without notice. Some restrictions may apply. Sincere feeling of caring are provided on an "AS IS" basis without warranty of any kind, express or implied, including, but not limited to the warranties of actual feelings of caring which may be replaced by feelings of hatred at any time without notice.

[2] Does not include travel and lodging expenses.